The post Wood Distortion: Five Fast Facts appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>

1. What’s in a name? To say that your board has “warped” is not really very descriptive nor useful. There are specific names that help us understand what type of movement is occurring, and that helps to define how to deal with the distortion. The bad news is that these conditions are not rare. The good news is that once a piece of wood gets to about a 12% moisture content, the gross movement stops — it has “stabilized.”

2. Our first term is “cup.” This is most common in flat or plainsawn lumber. The board stays reasonably flat in its length, but it curves across its width, away from the heart of the tree. Simply put, there is more shrinkage on one face of the board than the other. Once the wood stabilizes, use a jointer to flatten the face opposite the crown of the cup. Then run the board through a planer.

3. “Bow” describes a board that is flat across its width but curves in length: like a classic bow that powers an arrow. Once this board reaches equilibrium, the best way to make use of it is by cutting the board into very short pieces. The short length lessens the effect of the bow. You will still need to prepare the stock to be useable, but by starting with the short pieces, more material will remain useable.

4. “Spring,” often called “crooked,” means the board faces are flat in length and width, but from above the edges look a bit like a stream meandering around a bend. To produce the most material from this distortion, cutting the board to shorter pieces is again a first step. Then, straighten an edge, on a jointer or with a straight-line jig, so you can complete your stock preparation.

5. A “twist” is just what it sounds like. The board curves both in length and width, a bit like a corkscrew. This is perhaps the worst of all the possible distortions, and there is little to do to salvage a large, twisted board. You can, of course, chop it into small enough pieces so that the distortion is not evident (and there is always the fireplace or woodburning stove).

The post Wood Distortion: Five Fast Facts appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>The post Scroll Saw: A Serious Tool for a Serious Shop appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>In the world of tools, where bigger often means better, this small-sized saw gives little evidence of its large-sized capabilities. Because many types of projects can be cut with the scroll saw (a good thing), it’s defined primarily by what it can make, rather than by what it can do (a not-so-good thing). As a result, its use as a versatile shop tool is largely ignored. Here’s some information to fill in the gaps and motivate you to dust off, and perhaps even upgrade, your scroll saw.

Scroll Saw or Band Saw?

When making curved cuts, most woodworkers think “band saw,” rather than “scroll saw.” Both use a variety of blades,and both can make angled cuts of up to 45˚. The band saw clearly has the advantage in power and size of stock that can be handled. However, it cannot make internal cuts without cutting in from the edge. Even if made with the grain and glued carefully, such cuts remain visible on the sides of the wood. In addition, setup and blade changes are time-consuming, and the sharp blade can inflict damage if handled improperly.

The scroll saw is the tool of choice if workpieces are small or if fingers come close to the blade. Tasks such as cutting keys for miter slots are performed quickly, accurately and safely, requiring only two simple cuts per key.

The scroll saw also makes internal cuts and cutout areas with ease. To cut out an area, drill a blade entry hole, insert the blade, cut along the line, then smooth the edge with a spindle sander.

Additional Uses

The scroll saw can be used to cut the cheeks of a dovetail and to divide a wide tenon into two smaller ones. It can also cut the bottom curve of an apron for a small table or étagère. Use the saw to cut veneer for marquetry or to cut thin stock for double-bevel inlays. Give a box a decorative edge or integral feet, or simulate an inlay on a lid. You can even scroll a custom chain support.

As if this weren’t enough, you can always try a puzzle or other scrolled project, or make one with your child or grandchild. Unlike other power tools, the scroll saw provides a safe and engaging way to introduce a youngster to woodworking.

Before dusting off your scroll saw, assess the state of your scrolling skills. If they are rusty or nonexistent, bring them up to speed. Once learned, they can open the door to many fresh and exciting possibilities in your woodshop. Oh, and the answer to the original question? All of these projects were made with the scroll saw.

The post Scroll Saw: A Serious Tool for a Serious Shop appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>The post Using Shellac Inside and Outside of a Project? appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>

The cherry piece is a dresser with drawers. The Internet tells me that using oil-based finishes will give off fumes for a long time. This is why I was going to use shellac, but if there is another product that could be used on the inside of drawers without fumes and would not discolor the cherry, I would be open to trying something else.

– R. Clark

No, you don’t need to worry about blotching with shellac on cherry. And yes, oil-based finishes can leave a lingering odor, especially on interior surfaces. For that reason, among others, it is traditional to leave the insides of chests of drawers, and the insides of the drawers themselves, unfinished. However, if you choose to seal them, shellac is an excellent choice and will not impart any lingering odor once it is dry. In fact, shellac is often used to seal in odors that one can’t remove.

I’ll just add one unsolicited comment. While shellac is wonderful for many things, I’m not sure I would choose it for the top of a dresser. Spilled cologne, perfume, nail polish, nail polish remover or anything strongly alcoholic (rubbing alcohol) or alkaline (many mirror and “all surface” cleaners) can all damage and even remove shellac. Shellac is also prey to moderately high heat, from a hot coffee cup to a curling iron. Thus, for a top, you might want to seal it with one thin, flood-on/wipe-off coat of shellac, but for more durability, I’d top the top with polyurethane or conversion varnish.

The post Using Shellac Inside and Outside of a Project? appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>The post PROJECT: Shop-made Marking Knives appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>

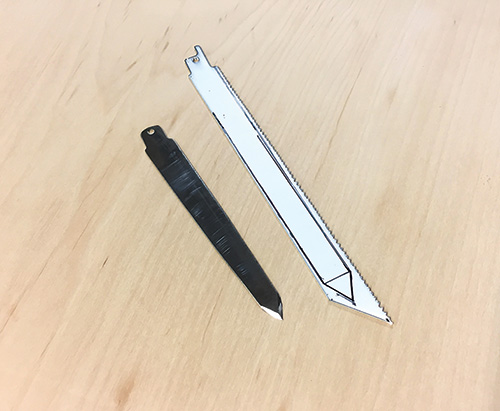

I was first introduced to handmade marking knives while studying under Tak Yoshino at the Mount Fuji School of Fine Woodworking in Yamanashi, Japan. He had made marking knives for his students out of some dull jigsaw blades he had lying around. When it came time for me to teach a class of my own, I decided to make a set of marking knives for my students just as Yoshino-San had done for me.

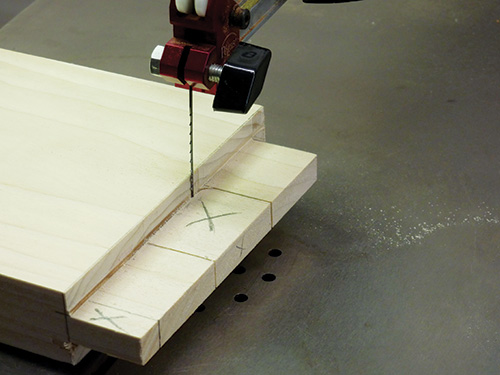

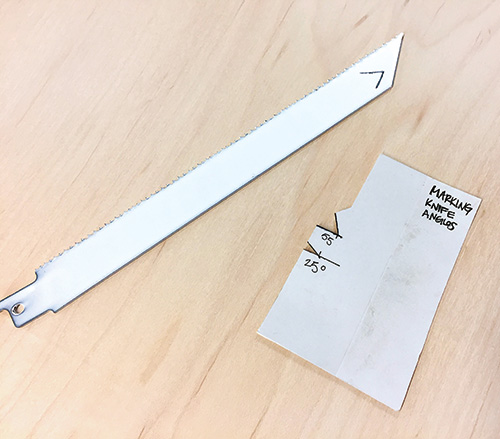

As blacksmiths are well aware, standard knife making involves a technical process of heat-treating and tempering to very specific degree to ensure strength and Rockwell hardness. For this reason, we will start with a prefabricated steel blade that has already gone through those technical processes in a factory. Blades for a reciprocating saw (Sawzall®), a jigsaw or a band saw work perfectly. To keep its temper, it is important not to overheat the blade as we are shaping it, just as when sharpening a chisel or any other tool.

For a standard sized marking knife, I start with a 6″- or 8″-long reciprocating saw blade that is around 3/4″ wide. Use one with smaller teeth, as they are easier to remove and leave you with more material in the end. A great option is an all-purpose bimetal blade that has 10 or 14 teeth per inch. You can also use an old dull blade of any size; use a jigsaw blade for a tiny tool or cut out a blank from a table saw blade for a heavy-duty knife. Stay away from anything carbide-tipped, as it will make the teeth much harder to remove.

Safety First

Ensure proper safety by working in a well-ventilated area clear of any flammable items. Wear safety goggles and a respirator. Wear gloves and use pliers when handling hot blades. Wear nonflammable clothing, such as cotton, and tie back long hair.

Preparing the Blade

The first tool we will use in this process is an angle grinder fitted with a 100-grit sanding disc or a flap wheel. Use extreme caution when working with this tool and always wear proper safety gear. Clamp the workpiece securely in a metal vise when working. When grinding material, move the tool in slow, steady motions from one end to the other; a rapid back-and-forth grinding motion will create an uneven edge.

The first step is removing the teeth and any paint or finish from the blade. Be sure to work in a well-ventilated area when removing paint. Clamp the blade in a heavy vise and remove the teeth with an angle grinder. Depending on the length of your blade and the size of your vise, you may need to reposition the blade several times to ensure strong pressure. Once the teeth are removed and the blade is safe to handle, strip the paint or finish from the blade. This can be done with an angle grinder while the blade is clamped in a vise or onto a table, or with the use of chemical strippers or other means of paint removal. Once the blade is free from paint and teeth, we can start to shape the blank into what will become the marking knife.

Shaping the Blade

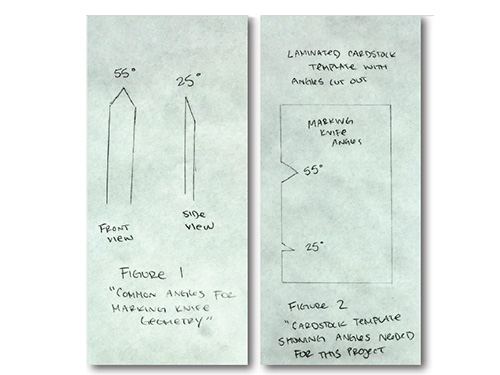

Start by using a permanent marker to outline the general shape of the blade. If you have an existing knife that you are duplicating, you can trace the angle and shape of the blade directly onto your blank or onto a template. I like to start by making a template out of cardstock with the proper angles cut into it so that I can easily create multiple matching tools.

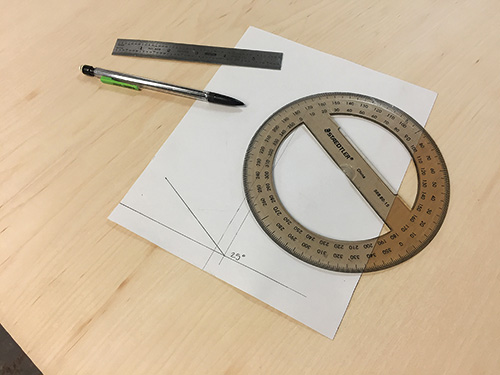

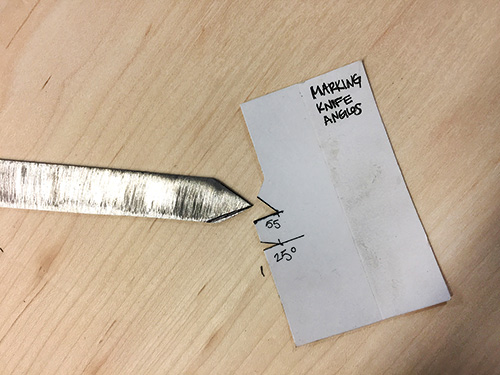

During the process of forming and sharpening the blade, it is helpful to refer to a template or guide to ensure the accuracy of the blade and grind angle. Marking knife angles generally range from 55° to 75°, with the angle of the ground edge ranging from 25° to 35°. I’ve found a 55° angle with a 25° grind makes a great all-purpose tool.

Using a protractor, mark the angle on a piece of cardstock and cut it out with a utility knife. Laminate the cardstock with clear packing tape to strengthen and keep the template clean. You will now be able to trace your angles directly onto your knife blank material.

Once you’ve drawn your outline, clamp the blank back in the vise. Using your angle grinder, grind away the blade material down to your lines, leaving a generous border on the pointed tip. Smooth the edges and round over the handle side of the blade using an angle grinder, a belt sander or a file.

Your blade should now mostly resemble your desired shape. Hold the tool in your hand to ensure its comfort and smoothness, and take down any rough spots with a file. From this point forward, we will focus on the cutting edge of the blade.

Sharpening Your Knife

The next tool in this process is a bench grinder, just like one that you may use to sharpen your other shop tools with. Wear safety goggles and a facemask as well as gloves while working on a bench grinder. Ensure the flatness of the wheel using a grinding wheel dressing stick before beginning. It is very important to keep the blade cool while working to avoid overheating and weakening the steel. Any change in color of the steel is a sign that the metal has been compromised and will not hold a sharp edge. Some bench grinders have builtin coolant systems. If yours does not, keep a jar of water near your grinding station and quench the blade tip every few seconds.

Check the angle of the blade using the cardstock template and re-mark if necessary. Grind the tip down to the marked line, checking the angle accuracy often. Once the proper angle has been achieved, check the flatness of each side with a straightedge. Depending on the quality of your grinding wheel, you may have to use a diamond-coated sharpening stone to flatten each side, ensuring the correct angle in the process. Once the sides are flat and true, the next step is to remove material and shape the blade angle.

On the bench grinder, set the guide to the grind angle (25°) with the help of a sliding protractor. Grind away the material in small passes, taking care not to overheat the blade. Use the template you made earlier to check the angle of the blade. Do not remove the blade material down to the very edge at this time, but instead leave a hair’s width so that a burr does not begin to develop on the back side. The rest of the process will be done with sharpening stones, so try not to leave so much excess that it will take a long time to remove with a stone.

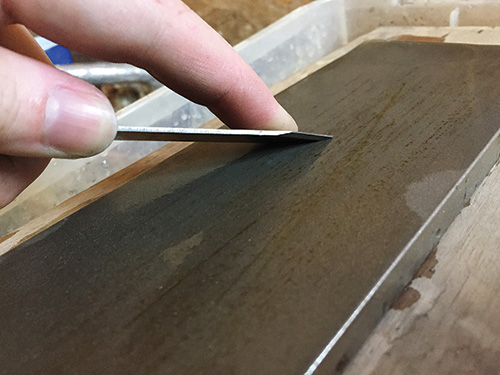

Sharpening with stones by hand requires intense focus as well as a sensitive touch, so take a few deep breaths before this next process. Find a comfortable body stance and be sure that the height of the work surface does not lead to pain in the neck or shoulders. Find a smooth, rhythmic process, gliding the tool back and forth along the stone. My teacher, Yoshino-San, used to tell us to “put your eyes and ears on the tips of your fingers” when sharpening. This process gets easier with practice, so if you are feeling frustrated at this point, stretch your arms and take several deep breaths before starting again.

Choose a coarse diamond-coated sharpening stone to use first. Applying even and gentle pressure, flatten the back side of the tool until the back of the blade area shows consistent markings. Turn the blade over and focus on the tip edges, next. Sharpen each edge, aiming for one flat surface. Do not yet go all the way to the edge of the blade, as the diamond stone is too coarse and will break the tip on a microscopic level. Check the angle of the edge against the cardstock guide often and, once the tool is flat and true, move to using a series of waterstones.

Starting with a 1,000-grit waterstone, sharpen each blade edge until a burr forms on the back. Move in steady motions, focusing on keeping the blade edge flat against the stone. Once a small burr has formed along the back edge of the blade, move to a finer 6,000- grit stone. Begin on the fine stone by removing the burr on the back side. Use gentle pressure to slide the blade back-and-forth several times along the stone, keeping the length of the blade flat against the stone. Just as before, sharpen each edge of the blade on the fine stone until a small burr forms.

Repeat this process of sharpening the edge, then removing the burr, a total of three times on the finest stone or until the knife’s edge holds a mirror polish. You’ll know you’re done when there’s no burr left on the final finish.

Finishing Steps

The marking knife is complete! Coat the blade with a tool oil such as camellia or jojoba oil to prevent rusting. (Camellia oil, also known as tea seed oil, comes from the seeds of Camellia sinensis, the plant that produces the tea we drink. It can prevent rust and lubricate machine parts — and it is also used frequently for cooking in southern China.)

Routinely hone the edge using the waterstones. If used properly and the tip remains unbroken, it will not have to be taken to a diamond stone or grinder again.

You can make a handle for your blade by epoxying wooden scales to the sides of your knife or by wrapping the handle area with leather cord. Make a small sheath out of cardstock, canvas or leather scraps to cover the tip of the blade.

Teresa Audet is a Minneapolis artist and educator working in wood, metal and fibers. She has taught at the Minneapolis Women’s Woodshop and was recently a Studio Fellow at the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship in Maine. Her website is teresaaudet.com.

The post PROJECT: Shop-made Marking Knives appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>The post PROJECT: Contemporary Hall Table appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

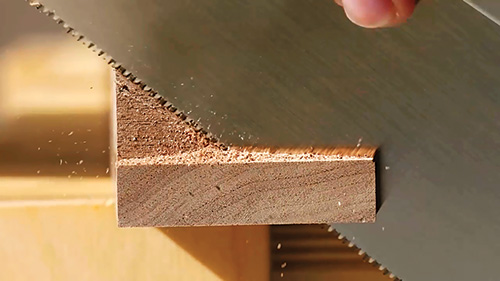

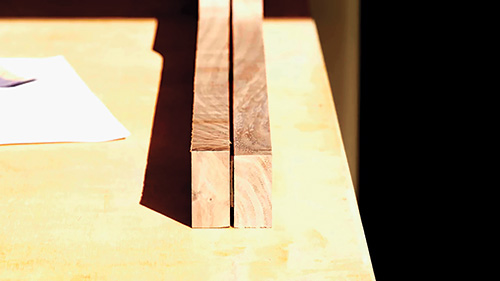

]]>I chose to make my table out of walnut. After cutting my walnut lumber into manageable sized chunks, my first building task was to work on the legs. I ripped a board of walnut into two pieces, each of which could yield two legs for this pretty standard style of four-legged table. I first crosscut the boards to the legs’ finished length of 29-5/8″ on the table saw. I made these cuts with my miter gauge set to 5°, which is the angle of splay I wanted to maintain.

You might notice also that these legs are subtly tapered. I laid out my desired taper on the leg boards, marking lines that tapered from 2″ at the top of the legs to 3/4″ at the bottom. I lined up these marks on my tapering jig and then ripped all four legs using the jig.

I also needed to rip the upper cross braces to width; they connect the tops of the legs. I’m reaching the point in my woodworking where I want to experiment more aesthetically. In the past, I probably would have cut these pieces out of stock the same thickness as the legs. This time around, though, I made them from thinner stock.

My next markups were to lay out the joinery: I used one of the cross braces I had cut to mark out the notches in the legs where the cross braces are joined to the legs, and I also marked out the location of a dado on the legs that will hold the low shelf. See Drawings for the location of the dadoes.

I machined the dadoes and notches on my table saw using a dado blade and miter gauge. Cut them at 5° to the edge (again, see the Drawings). Now it’s time to cut the cross braces (mostly) to length; I left them just a tad over-long so that I’d be able to use a hand saw to cut the angle to match the legs and sand them flush during assembly.

Body Building

I then turned my attention to the casework portion of this table. My material for the table sides, bottom and back — because I had it on hand from other projects — consisted of walnut plywood, with hardwood strips to cover up the plywood edges.

Obviously, if you have hardwood on hand or prefer to use it for the entire project, go ahead. I, on the other hand, roughed out the pieces for the back, bottom and sides, then I ripped and glued on the hardwood strips. Once they were dry, I sanded them flush.

I cut a 45° bevel on both ends of the long bottom piece and on the bottom end of each of the short side pieces. I also cut a 1/4″-deep by 3/8″- wide rabbet along the back edges of the plywood pieces, which will eventually capture the back panel.

My next step was to glue up the casework. I laid my boards out flat and end to end: the ends of the sides and bottom that are joined together with bevels were taped together with blue masking tape to serve as temporary “hinges.”

I applied a thin coat of glue onto both faces of these joints, then folded the assembly up into its correct shape. I used a long bar clamp to hold the ends and bottom square to one another while the glue dried.

As that cured, I sanded and finished those pieces that would be hard to access once assembly was complete.

Hardwood Components

My next cuts, made the following night after work, were for the table’s top and the shelf. I left the shelf oversized at this point, in order to do more assembly later on in the building process.

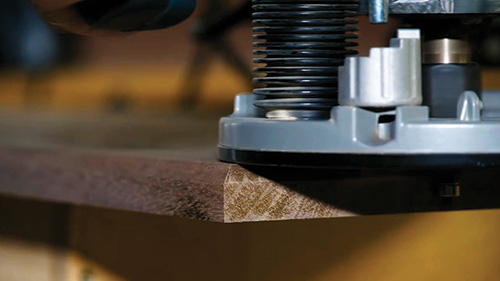

The top, however, was cut to final dimensions (see Material List). I then used a chamfer bit in my router to cut a 45° chamfer on the underside of the table’s top. It’s a bit more subtle than my usual sharp bevels, but again, it was part of my aesthetic experimentation with this piece.

The decorative stretchers, made next, are both structural and add an attractive detail: they support the long plywood pieces to help prevent sagging. I marked out one of these pieces, then made the cuts on the band saw — sort of.

My band saw blade was too wide to get close to the radius I had drawn, so I just nibbled close to the line, then sanded the rough area to the line to complete the shaping. Since I wanted the decorative stretchers to match, after I had finished with the first one, I used it as a guide for tracing onto the second blank.

I was then able to rough the second one out on the band saw. From here, I taped the two together and template-routed the second stretcher to match the first.

Assembling the Table

With all pieces cut, except for the drawer, I was ready to start assembling my table. The legs are attached directly to the casework sides using screws — they’ll be hidden by the drawer.

To install the stretchers, I secured them with a screw driven down through the drawer carcass at the center point of each stretcher. I also drove screws through the legs and into the ends of the stretchers, but this created visible screw holes. To camouflage their screw heads, I first drilled a recess (sometimes called a counterbore) at each screw hole with a 3/8″ bit, creating a place for the screw heads to “hide,” then I cut tapered screw plugs out of my scrap wood from the project to cover up the holes. Once I made sure the grain orientation matched the rest of the surface and sanded down the plugs, they became pretty much invisible — unless you look really, really closely.

My method of choice for attaching the walnut table top to the rest of the plywood casework was four Domino joints. (If you don’t have a Festool Domino machine, you can use dowels and get good results, too.) The Dominoes go from the top of the plywood into the underside of the top. After making the cuts in the plywood, I rested the top in position in order to mark where the cuts on the underside would need to be.

With that done, I was still not quite ready to glue the top down. Instead, I first installed the shelf between the legs, fitted into the dadoes I made earlier. I cut the shelf to size by referencing the space between the dadoes in the legs. The shelf, like the stretchers, is attached with screws, which are then hidden with plugs. (I figured I was already making the other plugs, why not just make more?) With the shelf in place, I attached the top.

Building the Drawer

As you may have noticed, I’ve been mentioning that this table has a drawer — and its construction is next up. The drawer is just a simple box that slides tightly into the cubbyhole created by the casework. No rails, no hardware. The front and back pieces get a rabbet to accept the drawer sides, and the drawer side pieces get a groove for a bottom panel.

I used hardwood for the front panel and 3/4″ plywood for the sides and back. It probably would have been more appropriate to use 1/2″ plywood or solid stock but, again, I was just making use of whatever I had on hand.

I rough-cut all the drawer pieces slightly oversized. Then I planed the solid walnut front panel down to about a 1″ thickness. I carefully fit the drawer front piece (cutting, then test fitting) to get it to the exact width it needed to be. I used that setting on my table saw to cut the drawer sides to their exact widths as well.

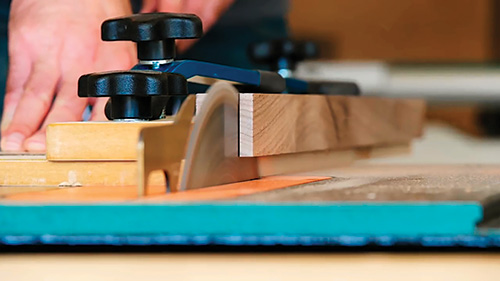

I used the same fit-and-cut process with the drawer back piece to find the exact length I needed and transferred that over to the drawer front. This drawer needs to fit the opening snugly. I marked out the rabbet on the drawer front to fit the plywood sides. Stepping to the table saw, I cut these rabbets by first crosscutting on the table saw, then employing a jig to run the piece vertically for the second cut to complete the joint.

I then plowed the grooves that hold the bottom in the side pieces and used that mark to determine how wide to cut the back piece to finalize it. That’s because the drawer back is narrower than the sides and front so that the bottom panel can slide in under the drawer back and be pin-nailed securely to it after the drawer is assembled. (You can find these measurements in the Drawings.)

Before assembling the drawer, I shaped a cutout on the drawer front to act as a drawer pull. I made this negative space cutout on the table saw so that it fit my hand. I also shaped a small rabbet around the perimeter of the drawer front to make the reveal between the drawer and the forward edges of the carcass a little more uniform and to provide a nice shadow line. With this work behind me, it was finally time to glue up and assemble the drawer, putting the drawer bottom in last. Be sure your drawer box is square when clamped up.

Final Assembly Details

As the drawer box glue-up was drying, I attached a 1/4″ plywood back panel into the carcass opening formed by the rabbets I had cut earlier.

Now it was time to do the final sanding and apply a finish. For this project, I opted for several coats of drying oil followed by a coat of paste wax. Oil and wax is a great solution to warm up the walnut’s color, and the finish is easily touched up, if needed. This was a fun project to build and, call it what you will, it now looks great in our hallway.

Click Here to Download the Drawings and Materials List.

Chris Salomone got into woodworking and designing furniture in 2008, when he and his wife bought a house and needed to fill it. This led to community college woodworking classes, then to building custom furniture through his foureyesfurniture.com business, and then to his YouTube channel, where he hopes to entertain and inspire you with the videos of his designs and builds.

The post PROJECT: Contemporary Hall Table appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>The post PROJECT: Router Table Cabinet appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>Click Here to Download the Drawings and Materials List.

This organizer fits Rockler’s Router Table Steel Stand.

Building the Center Drawer Cabinet

Let’s kick this project off by cutting the drawer cabinet’s top, bottom and sides to size. You’ll notice in the Drawings that the top and bottom panel require 3/4″-wide, 3/8″-deep rabbets milled into their ends to fit the side panels. Cut those rabbets now with a wide dado blade buried partially in a sacrificial fence at the table saw.

Dry assemble the top, bottom and sides so you can take final measurements for the back panel — it simply butts against the back of the cabinet rather than fitting into it. Cut the back panel to final size.

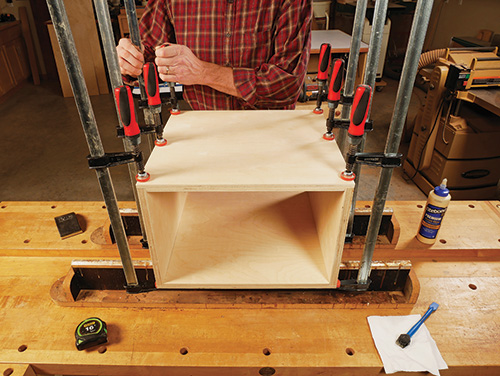

I decided to install the cabinet back using pocket screw joints, so I bored four holes into the inside faces of each cabinet side for this purpose. If you don’t have a pocket screw jig, you could attach the back with brads, screws or even glue alone, if you’d rather not see fasteners. Give the cabinet part surfaces a light sanding, then spread glue along the top and bottom panel rabbets, and assemble the carcass with clamps.

When the glue dries, attach the cabinet-side drawer slide components to the side panels with screws. Center them vertically, making sure they’re parallel with the cabinet top and bottom so the drawer will slide smoothly. A couple of scrap spacers can make this process easier and more foolproof than aligning the hardware by measuring.

Install the back panel on the cabinet. Its edges should be flush with the outside edges of the carcass.

Making the Drawer

On a shop project like this, I like to keep drawer construction simple but strong, and there are other options besides dovetails. While they aren’t the fanciest choice, rabbet-and-dado joints have stood the test of time for me, so that’s what I used for this drawer. Start the construction process by cutting the front, back and side panels to shape.

A 1/4″-wide dado blade, raised 1/4″, will take care of all the cuts you’ll need to make for the corner joints and drawer bottom groove. Set your table saw’s rip fence 1/4″ away from the blade, and cut a dado across the inside face of the side panels on both ends. Now, without moving the fence, cut a drawer bottom groove along the inside face of the front, back and side panels.

Install a sacrificial facing on the rip fence, and slide it over until the dado blade just “kisses” the fence facing; this sets up the rabbet cuts for the corner joints. Make a test cut on a scrap piece of 1/2″ plywood, and see if it fits the drawer side dadoes. Raise or lower the blade a nudge, if needed, so the rabbets will fit their dadoes snugly. Cut rabbets across the ends of the outside faces of the drawer front and back, to complete these joints.

Dry assemble the drawer box, and measure the length and width of its inside opening. Add 1/2″ to each of these dimensions, and you’ll have the final proportions for the drawer bottom panel. Cut it to size.

Reinstall the 1/4″ dado blade and sacrificial fence again and, with it raised 1/4″ above the table, mill a rabbet around all four sides of the bottom face of the drawer bottom panel. Test your setup first on a scrap to be sure the rabbet proportions are dialed in correctly; you want the drawer bottom rabbets to fit their grooves so the panel seats inside the drawer box but still allows the corner joints to close completely.

Sand the drawer parts smooth, and assemble the drawer with glue and clamps. All the surface area of these joints will ensure that the drawer will be plenty strong without any added fasteners. Check it for square by measuring the diagonals. Adjust your clamps, if needed, until the diagonal measurements match.

When the clamps come off, attach the drawer-side slide components to the drawer sides, centering them vertically and making sure they’re parallel. Now install the drawer in the cabinet to check its sliding action. If all is well, cut a drawer face to size; the Material List dimensions account for the drawer face having 1/16″ of inset on the sides and bottom of the cabinet opening to provide clearance when the drawer is opened and closed.

I attached the drawer face to the drawer box with several strips of double-sided tape to align it right where I wanted it, checking its position with the drawer installed in the cabinet. Then, I marked the face for the drawer pull and drilled a pair of 3/16″-dia. holes through both the drawer face and the drawer front. The holes in the drawer face, of course, allow for the wire pull’s installation screws. The holes in the drawer front serve a different purpose: here, I enlarged these holes with a 1/2″ Forstner bit. This way, once the wire pull is installed and the drawer face is mounted on the drawer, I’ll always have access to the wire pull’s screw heads from inside the drawer, should they ever loosen up (and often, they do). I used four 1″-long washerhead screws to attach the drawer face permanently. The top two screws were installed first into oversized holes in the drawer front to give me a final bit of adjustability before driving the bottom two screws into regular screw clearance holes.

Constructing the Bit Racks

The two bit racks are identical, so go ahead and cut four tops, bottoms and sides to size. Then, just as you did for the drawer cabinet, load a wide dado blade in the table saw to cut 3/4″-wide, 3/8″-deep rabbets. Cut rabbets in the top and bottom panels for the side panels, then cut a rabbet along the inside back edge of the tops, bottoms and sides for the back panels.

Each side panel also receives 1/8″-deep, 3/4″-wide dadoes cut across the inside face for four bit shelves. Make sure to adjust the width of your dado blade, as needed, to match the thickness of the 3/4″ plywood you’re using for this project — its thickness is probably closer to 23/32″, and you want the bit shelves to fit their dadoes without gaps. Follow the Elevation Drawings on the next page to space these dadoes apart evenly. I cut them with the shelves backed up against a long fence attached to my saw’s miter gauge, using a stop block to set the position of each cut. Flipping the side panels end for end will enable you to make two dado cuts per stop block setting.

With the joinery completed, fit the bit racks together temporarily so you can determine the final dimensions of the back panel and the length of the shelves. Cut the two back panels and eight shelves to size.

All that’s left to do before final sanding and assembly is to drill holes in the shelves and bottom panel for router bit shanks. I’m using Rockler’s new plastic Router Bit Storage Inserts, which will hold either 1/2″- or 1/4″-shank bits.

Over the years, I’ve found that 2″ spacing between bits works well for storing practically any router bit you’ll run across, and that spacing will fit seven bits per shelf here. Mark the shelves and bottom panel according to my spacing (or your own, as you see fit), and drill centered holes for the bits. If you use Rockler’s inserts, these holes are 5/8″ dia. and should be bored all the way through the shelves and bottom panels.

Sand the bit rack components, and assemble the tops, bottoms, sides and back panels with glue and clamps.

Finishing and Installation

Next, I cut a base panel to size. This was also a good time to build a small holder from scrap for storing my router lift’s five aluminum insert rings. After that, I laminated three pieces of 1/2″ plywood together, with a 5/16″ x 5/16″ groove cut along the length of the center piece, to stow my router lift’s height adjustment wrench. It’s easer to install features like these before the racks are in place on the router table, so consider doing the same for your organizer now, with any add-ons.

Remove the drawer slides and wire pull, and you’re ready to apply finish. I used General Finishes water-based High Performance varnish, which applies beautifully with a brush or foam roller and dries quickly. When the finish cures, push the plastic bit inserts into their shelf holes.

To install the organizer, first remove your router lift. I also removed the metal Dust Bucket enclosure around the router motor. Fit the base into place on the router table’s lower cross supports. Rockler provides screw holes if you want to fasten the base to these supports, as I did, driving 1/2″ panhead screws up into it from below. Slide the bit racks and drawer cabinet into place on the base; they’re inset 1/4″ from the base’s edges and ends. Mark the location of the components on the base, and drill pilot holes down through the cabinet bottom into the base for screws. If you have an enclosure around your router, pull the cabinet back out and reinstall the enclosure now. Then slide the cabinet back into position, and fasten it to the base with countersunk screws. Drive more screws through the side walls of the cabinet and into the backs of the bit racks to secure them.

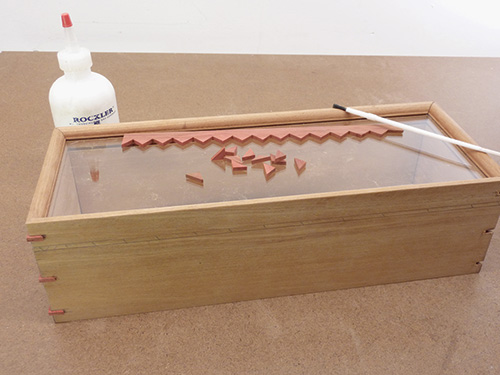

Sooner or later, you’ll want to have a pair of featherboards close at hand for router table operations, and here’s an easy way to store them. I fastened a length of Rockler’s extruded aluminum miter track to the cabinet back, 1-1/2″ down from its top edge. It makes a simple holder for several large featherboards: just tighten one of their expanding miter bars into the track, and they’ll be at the ready when you need them.

Click Here to Download the Drawings and Materials List.

Hard-to-Find Hardware:

Centerline® 14″ Full-extension Drawer Slides (1) #44506

4″ Brushed Satin Nickel Wire Pull (1) #1010901

Router Bit Storage Inserts, 10-Pack (7) #57223

Rockler 36″ Miter Track (1) #48037

The post PROJECT: Router Table Cabinet appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>The post PROJECT: Krenov-inspired Shop Cabinet appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>The post PROJECT: Krenov-inspired Shop Cabinet appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>The post Woodworker’s Journal – January/February 2019 appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>The post Woodworker’s Journal – January/February 2019 appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>The post VIDEO: Contemporary Hall Table appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>See more of Chris’ work on his website and check out his YouTube channel for more great projects.

The post VIDEO: Contemporary Hall Table appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>The post Scroll Sawn Nightlight Patterns appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>Click Here to Download the Plan.

The post Scroll Sawn Nightlight Patterns appeared first on Woodworking | Blog | Videos | Plans | How To.

]]>